Back in March of this year, any column I would’ve written could’ve only been titled “Why I should’ve gone to [insert SEC school here].â€

As I left Tobacco Road on Glenwood Avenue after watching yet another State basketball season mercifully end – like so many years before it – on the Thursday of the ACC Tournament, I decided I needed a break. I was burned out, drained. Last season was neither fun nor exciting, and I’d become so negative towards State basketball that, for the first time in my life, I wanted to be emancipated from it. So I went on a three-month hiatus: no SFN, N&O, or WRAL and no Sidney Lowe, Lee Fowler, or John Wall.

The problem is I’ve never been anything but a State fan. But more importantly, I want to be a State fan. Sometimes a reprieve is all we need, and right around the middle of May, right when I was (somewhat begrudgingly) cutting my check for my LTRs and season tickets, I realized I’m far more excited about the upcoming football season than is probably prudent, especially based on my lifetime of experience that suggests I should reign in my excitement and exchange it instead for cautious optimism.

Growing up in North Carolina you’re socialized to revere Tobacco Road basketball with what borders on spiritual awe, while football only seems to really matter when you’re winning – it’s like SEC basketball. State football has never enjoyed anywhere near the same religious fervor reserved for its storied, proud basketball tradition. My generation – I was born in 1979 (coincidentally, the same year as our last conference title) – has experienced even less success in football than basketball (however possible), so why do we continue to always have such high expectations before each season? It can’t be just the tailgating – can it?

The five-part series that follows is by no means intended to be authoritative. Rather, it’s nothing more than an incomplete, inconclusive, sometimes erroneous, while always biased retrospective of recent State football history. Part of this was based on nothing more than my attempt to answer the question so many of us are left asking year after year: How did we get here?

Part I: The 90s

The synopsis of State football during the 90s is actually quite succinct. We won games we shouldn’t have won and then promptly lost games we shouldn’t have lost, while Mike O’Cain committed the Seven Deadly Sins for any head coach at North Carolina State: he lost to Carolina seven times consecutively. And while the basketball program’s once proud tradition dissipated into oblivion during the 90s, the football program remained a steady but hardly-noticeable presence on the national scene.

The synopsis of State football during the 90s is actually quite succinct. We won games we shouldn’t have won and then promptly lost games we shouldn’t have lost, while Mike O’Cain committed the Seven Deadly Sins for any head coach at North Carolina State: he lost to Carolina seven times consecutively. And while the basketball program’s once proud tradition dissipated into oblivion during the 90s, the football program remained a steady but hardly-noticeable presence on the national scene.

Neither Dick Sheridan nor O’Cain had any sustained bowl success during the decade; the two combined for a bowl record of 2-7. Sheridan’s teams defeated Brett Farve’s Southern Mississippi 31-27 in the 1990 All American Bowl, but then toiled over the next few years; on New Year’s Day 1992, East Carolina mounted a comeback on the wet, natural turf of the old Fulton County Stadium to defeat State 37-34 in the Peach Bowl; a year later, somewhere mired within the New Year’s Eve fog of the 1992 Gator Bowl, Florida’s Errict Rhett rushed for 182 yards in a 27-10 romp over State. After Sheridan’s untimely retirement just a few weeks prior to the 1993 season, O’Cain’s first team was shellacked 42-7 by Michigan in the 1994 Hall of Fame Bowl, where Tyrone Wheatley rushed for 124 yards and two touchdowns.

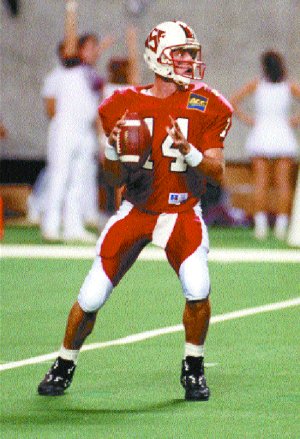

Terry Harvey in the 1995 Peach Bowl

At least until State gave them no more reason to ring them.

State rallied late, tying the game at 21 going into the fourth quarter on a three-yard touchdown pass from Terry Harvey to Dallas Dickerson. On the ensuing drive, the defense – led by eventual game MVP Damien Covington – forced a quick three-and-out. State promptly finished the rally with a quick-strike four-play, 80-yard drive set up by a 62-yard reception by Jimmy Grissett, and then capped off by an 11-yard Carlos King touchdown. But it wouldn’t end without drama: Mississippi State added a late field goal to pull within 28-24, and then after forcing a punt within the final two minutes, quickly drove the ball inside the State 30. But amidst the threat of all the deafening, inharmonic clanking of cowbells, State’s defense held firm and secured victory by forcing a turnover-on-downs in the waning moments.

Finally, those “damned cowbells†had fallen silent. On the MARTA afterwards, one State fan cracked loudly that he didn’t hear any of those “damned cowbells†anymore. A few feet away, in a final act of defiance to the victors and loyalty to the defeated, a young boy rattled his cowbell one last time, which triggered uproars of laughter from both the victors and the defeated.

It would be one of only two watershed victories under O’Cain, who was unable to build on the promise of that Peach Bowl victory, and State football promptly faded again into the background after consecutive records of 3-8 in 1995 and again in 1996; State finished 6-5 in 1997, but out of the bowl picture, since that was back when only deserving teams were rewarded with a bowl (instead of any team with a .500 record and willing to go to Boise in December). But then, early in the 1998 season, we could finally sense the breakthrough we’d all been waiting for. After squeaking past Ohio University 34-31 in an uninspiring opener, O’Cain led State to the biggest win of its football history.

On September 12, 1998, a mere 20 seconds into the game, second-ranked Florida State’s Chris Weinke delivered a 74-yard touchdown strike to Peter Warrick on the first play from scrimmage. State responded with a long but fruitless drive that ended after a missed field goal. Then, on Florida State’s ensuing drive, Weinke had first-and-goal on the five.

Let’s pause here a moment, because without the proper context, the significance of this moment is lost. See, in the six games since Florida State had joined the ACC in 1992, the Seminoles had outscored the Pack 306-88, which translates to an average score of 51-14 (1992, 34-3; 1993, 62-3; 1994, 34-3; 1995, 77-17; and 1996, 51-17). The only outlier had been the previous year in 1997 in Tallahassee, when second-ranked Florida State was perhaps caught looking past us towards its hyped-up trip to Chapel Hill the following weekend to face fifth-ranked Carolina. The Seminoles pounced all over the Pack early, commanding a 27-0 lead after the first quarter. But then, as a freshman, I watched from my Owen Hall dorm room as over the next three quarters, Florida State got its first dose of Jamie Barnette and Torry Holt. The duo connected for five touchdowns, and it could have been more, if not for two Florida State interceptions of Barnette in the end zone. But State still lost 48-35, and so this game seemed nothing but an outlier.

So here we were in 1998, standing in the student section on a typical sweltering September afternoon in my sophomore year, early in the first quarter, and for those of us keenly aware of the history of this series, 14-0 and another blowout was a foregone conclusion – we’d be out at the truck eating Bojangle’s by halftime. Weinke was business-as-usual, poised to settle into his groove.

Fortunately for us, that groove was the State secondary. On first-and-goal from the five, Weinke connected with Tony Scott on the one yard line, and State never looked back. We responded with a staggering 10-play, 99-yard scoring drive, capped by Barnette’s 31-yard touchdown pass to Eric Leak (the original Owen Spencer, kids). Less than two minutes later, after the State defense forced a three-and-out, Holt unfurled that magnificent 68-yard punt return for a touchdown to give us a 13-7 lead after the first quarter. The rout was on. With 24 seconds left in the game, State led 24-7 and Bobby Bowden pulled his team off the field as a cessation of Florida State’s second conference loss as a member of the ACC.

I don’t remember exactly how long it took – it wasn’t long at all – but we helped topple the south end zone uprights and then marched them out of the stadium and across the fairgrounds before most of us fell out to go continue the celebration elsewhere. I don’t know how far the one upright made it exactly, but I remember hearing that it was found later that evening in the parking lot of the Hillsborough Street Waffle House, just the other side of the Beltline.

That win remains State’s biggest ever. Holt was again dominant, reeling in nine catches for 135 yards and adding another touchdown to his punt return. Meanwhile, Weinke was an abysmal 9-of-32 passing with six interceptions, three of which ended drives that had breached the State 35 in the fourth quarter alone. The sheer dominance of that defensive performance was only truly understood after season’s end, because Weinke didn’t throw a single interception the rest of the season and led Florida State to the Fiesta Bowl against Tennessee to decide the first BCS National Championship (although Marcus Outzen actually played in that losing effort, due to Weinke’s season-ending neck injury in November).

But true to the storyline that defines the N.C. State Saga, a week after beating Florida State (a game we shouldn’t have won) that same team suffered an embarrassing 33-30 loss to Baylor in Waco (a game we shouldn’t have lost); after an off week, on the first night of October – one of those perfect North Carolina early autumn evenings – we took down the new goal posts after defeating eighth-ranked Syracuse 38-17 in ESPN’s Thursday night game (another game we shouldn’t have won). The theme continued after we lost to Carolina in Charlotte (after a noble second-half comeback once O’Cain realized good things happen when you actually throw the ball to Holt) and then to Miami in the MicronPC Bowl, to finish the 1998 season at 7-5.

Add some silver pants and you've got a horribly misguided impression of Georgia

The 1999 season served as the perfect microcosm of the entire decade: win a game we shouldn’t win (23-20 over Texas in Austin), lose one we shouldn’t lose (31-7 at Wake Forest), and once again lose to Carolina (10-6 in Charlotte). O’Cain was finished. We’d been mediocre for the entire decade and apathy had taken a firm hold, evidenced by the Carter-Finley attendance over O’Cain’s final five seasons, which was never above 90% capacity. For an athletic department hell-bent on multi-million dollar renovations to the facilities, it was essential that the next coach be able to usher in the new millennium by immediately refueling excitement and drastically increasing funding based on nothing beyond hope and rhetoric.

Chuck Amato was the perfect guy for the job. He reeked of rhetoric.

You must be logged in to post a comment.